I HAD A COFFEE WITH AN ACQUAINTANCE the other day. She had invited me and others to her home for an after class get-together. Unfortunately, I was the only one who could attend, so I suggested we put it off. She wouldn't hear of it. My acquaintance is an interesting woman - intelligent, sophisticated, and a professor of English. She teaches Can Lit.

I have my own biases about Can Lit. As a genre writer, I find Can Lit a bit mundane for my tastes. I suspect she might find my work in speculative fiction over the top and sensational. At one point, she quoted a writer of whom she was fond (I can't remember who it was), saying that 'no one made him write. Nor did he expect anyone to pay him for a living.' I found the comment a little odd at the time, but I didn't question it. After all, she had invited me into her home for coffee.

In hindsight, I found myself thinking about this comment in more depth.

As writers, we understand the drive that makes us want to write. It comes from a variety of sources: the need to create being foremost, but also a desire to say something worthwhile, to entertain, to affect, to make our mark. If we are being honest, ego also plays a part.. If it didn't, we wouldn't care when others reject our work, nor would we shout from the rooftops when our stories are accepted for publication. I found myself wondering if her comment came from a less than generous source.

We don't expect people to pay us for our living, although it's nice when they do. We write, anyway, no matter what we are paid. That said, it is also important to be valued for what we do, because so often, we aren't. (In terms of popularity, hockey players get more respect here in Canada than artists do.) Very few of us are able to make our livings as writers, yet we persist. My friend thought she might like to try writing some day, she had never attempted it. I found myself hoping her comment didn't come from a place of envy or entitlement. Sometimes, those who can't or don't, envy those who do.

But the bigger problem that such a comment points to is this:

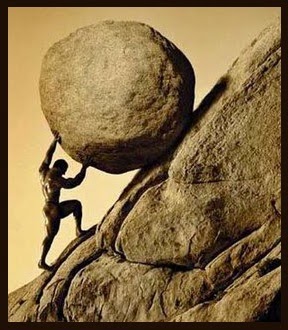

we often don't respect ourselves as writers or see the great value in what we do. We write for scraps - for next to no money, or for shreds of praise. If one of us comments 'no one makes me write. I don't expect to be paid for a living' then maybe we need to reconsider our worth. I've said it before on this blog.

Imagine a world without story, without music, without art. That is what all of us who attempt to create, contribute

to.

Maybe we

should expect more, demand more. Not give away our art for free. Granted, when we are learning, we need to make allowances for our apprenticeships. If we don't respect ourselves as artists, worthy of being paid and valued, how can we expect others to? Furthermore, if others outside our minority don't respect and support us as a community, we at least need to respect and support ourselves.

- Susan.